AI Adoption and the Rich-Poor Divide: An Ethical Dilemma

AI can be the great equaliser, or the ultimate divider. This thought-provoking read explores how AI adoption could bridge or widen the rich-poor gap, with global examples, a Singapore case study, and

This week in my BCG Digital Transformation and Change Management course, our team tackled a hackathon-style project on Robotic Process Automation (RPA). In just 48 hours, we went from concept to a future vision of where RPA, supercharged by AI, transforms industries overnight.

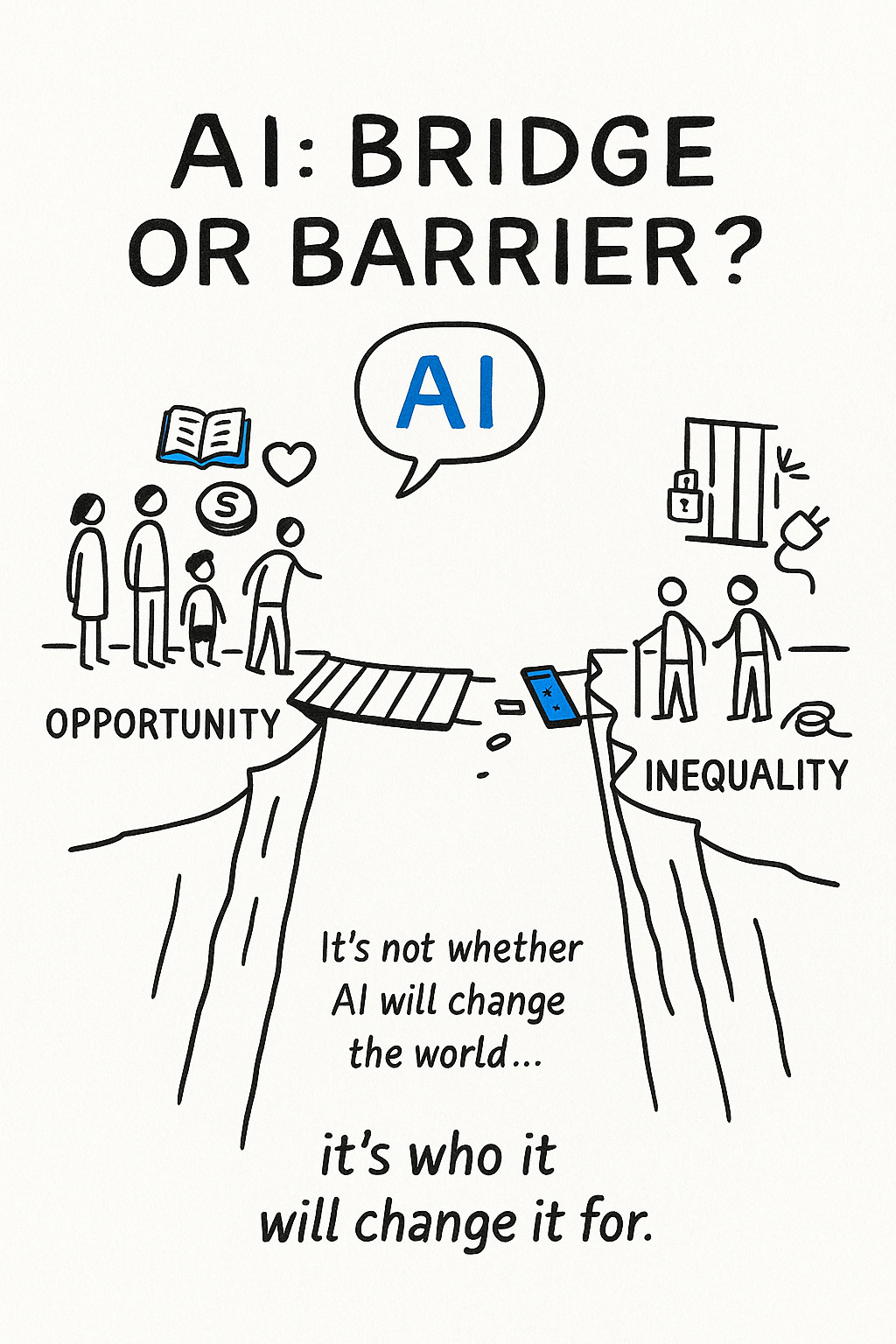

While we celebrated the promise of fewer errors, faster processes, and more innovation, it pulled me back to a conversation at last week’s Future Forward roundtable on AI ethics. The question wasn’t whether AI would change the world. The real question was: who would it change it for?

AI is often pitched as the great equaliser, delivering world-class healthcare, education, and economic opportunity to anyone with a connection. But it could just as easily become a great divider, locking progress behind paywalls and bandwidth speeds.

Here’s the reality: one-third of the world still remains offline. Meanwhile, advanced economies and tech giants are accelerating at full throttle in AI deployment.

This post explores AI’s double-edged sword, how it could bridge or widen the rich-poor divide, through global examples and a closer look at Singapore.

1. The Promise of AI: Levelling the Playing Field

If AI is built for inclusion, it’s not just a technology; it’s a social equaliser. Done right, it can shrink the distance between the privileged and the underserved, making access to knowledge and opportunity less about geography and more about design.

Access to Critical Services

In South Asia, Google’s AI-powered flood forecasting sends early warnings to vulnerable villages, giving families hours, sometimes days, to get to safety. In rural clinics, AI diagnostic tools can detect diabetic blindness and tuberculosis from simple medical images with expert-level accuracy. No specialist on-site? No problem. AI becomes the doctor who never sleeps.

Personalised Education for All

In parts of Africa, platforms like Eneza Education use AI to deliver lessons via basic mobile phones, working offline and in local languages. It adapts practice questions to each learner’s level, giving rural students the same personalised feedback a wealthy city kid might get from a tutor.

Financial Inclusion & Economic Empowerment

In Latin America, AI-driven fintech apps are bringing banking to the unbanked, using alternative data to unlock loans for micro-entrepreneurs. In rural communities, AI farming tools connect small farmers to buyers and provide real-time weather or crop health insights—turning subsistence farming into a more sustainable business model.

Why It Matters

AI, when designed for inclusion, is the cost-cutter for expertise. It slices through economic and geographic barriers to deliver life-changing knowledge and services to those who’ve historically been locked out.

2. The Perils of AI: Supercharging Inequality

But here’s the shadow side: without guardrails, AI doesn’t just mirror inequality, it magnifies it.

Between-Country Gaps

Wealthy nations dominate AI R&D and investment. In 2023, the U.S. attracted $67B in private AI investment, over eight times more than China which placed 2nd! Meanwhile, broadband in low-income countries can cost 30% of a monthly income, making access to AI-driven services a luxury.

Automation & Job Losses

In Bangladesh, the garment industry, which employs millions of low-income workers, faces up to 60% job losses by 2030 as AI-powered machines take over repetitive tasks. Globally, the IMF estimates 40% of jobs are AI-exposed. Advanced economies have safety nets and retraining programs. Developing nations often don’t.

Concentration of Power

The top AI firms (mostly in the U.S. and China) control vast datasets and computing power. The result? A monopoly on innovation where smaller nations and companies are left consuming, not creating, AI. As AI boosts efficiency, it might increase returns to capital more than labour. An example is when companies save on wage costs via automation, see higher margins, but workers see fewer job opportunities.

Bias & Exclusion

AI systems themselves can reflect and amplify societal biases, often to the detriment of marginalised groups. When Indiana automated welfare eligibility checks, over one million eligible applicants were wrongly denied. The lesson: if the training data is biased, the algorithm will be too, and it’s often the most vulnerable who get cut out first.

3. Case Study: Singapore – AI Leader, Ethical Crossroads

Singapore offers a microcosm of the AI inequality dilemma. We rank #1 globally in AI readiness (according to IMF) and have the fastest AI skill adoption rate in the world.

Inclusive Efforts

The government has heavily promoted digital transformation under its “Smart Nation” initiative, and Singapore’s workforce is considered the fastest in the world at adopting AI skills. Through SkillsFuture, Singapore offers subsidised training in everything from digital literacy to advanced AI, with extra support for older workers and people with disabilities.

On paper, Singapore is reaping AI’s rewards: automation is boosting productivity and innovation in sectors from manufacturing to logistics. However, the benefits and burdens of AI are unevenly distributed across different groups in Singapore, revealing ethical trade-offs even in a wealthy society.

The Other Side

As automation accelerates. The city-state’s lower-skilled income workers (including 1M migrant workers), who fill labour-intensive jobs in construction, cleaning, and domestic work, could be displaced without sufficient safety nets.

Singapore today is the second most robot-dense nation globally (730 industrial robots per 10,000 workers), and this automation has coincided with a steady decline in manufacturing employment even as output grows. There is a real risk that AI and robots will exacerbate socioeconomic divides, benefiting high-tech firms and skilled locals.

The ethical question: what responsibility does a nation have to the very workers who helped build it?

Key Takeaway

The Singaporean example underscores that even in a wealthy, tech-forward nation, deliberate policy is needed to ensure AI’s benefits are broadly shared and its disruptions are managed fairly.

4. The Balancing Act: How We Ensure AI Works for All

The dual nature of AI, as a potential equaliser and a possible divider, means we must strike a balance. The ethical dilemma at the heart of AI adoption is how to pursue innovation without sidelining the most vulnerable. Solving this requires conscious action from international bodies, policymakers, and corporations:

Global Collaboration

International bodies like the UN should treat AI inequality with the same urgency as climate change. That means funding AI-for-good projects, creating shared open-source models, and ensuring no country is left in the digital dust.

Government Policy

Internet access as a public good. Nationwide re-skilling at scale. Social safety nets for displaced workers. Antitrust measures to prevent AI monopolies. These aren’t nice-to-haves, they’re the foundation of an equitable AI future.

Corporate Responsibility

AI firms must design for fairness, transparency, and inclusion. That means building with diverse datasets, running bias audits, and engaging communities directly in the design process. The most impactful AI solutions will come from co-creation with the people they aim to serve. Remember human-centered design? It’s not just recommended, it’s the right thing to do here.

Final Thoughts: The Ethical Test of Our Time

AI’s global spread is more than a technological shift. It’s a values test. Will it be the great equaliser, extending opportunity and prosperity to those who need it most? Or will it act as a turbocharger of inequality, widening the chasm between the haves and have-nots?

The answer depends entirely on the choices we make now.

The promise is clear: with creativity and compassion, AI can lift communities, be it a farmer receiving real-time crop advice that saves a season’s harvest, or a student in a slum accessing the world’s best tutors through a mobile phone.

The risk is equally stark: without deliberate action, the default trajectory leaves the marginalised further behind. A factory worker replaced by automation, a developing nation excluded from the AI-driven economy.

Ultimately, the rich-poor AI dilemma comes down to one principle: inclusion by design, human-centered design. Technology alone doesn’t guarantee progress. It’s only equitable when built on human-centred design that actively works to include, not exclude.

AI isn’t destiny. It’s a mirror. What it reflects back will be less about algorithms, and more about the values we code into them.